“How words do things with us?” is the title of chapter eight. It starts with the idea of how the virtual machines inside us are organised and how they could have a “virtual captain” of the crew, but not elevate the captain to have dictatorial power. Dennett starts from here to neutralise any possible illusion of the central meaner. How can the Cartesian Theatre be overcome in the field of language production? Language production is a challenge because, in the end, there’s only one final report issued by our minds and pronounced as speech. Does that mean we have a central meaner that decides what is said? If this isn’t the case, do we have different internal machine states that produce meanings with rules to govern that process? In this chapter, Dennett’s main task is eliminating that central meaner.

Dennett draws our attention to what he believes is a problem in contemporary linguistics and speech production. The field is full of appreciation for the art of speech, but it never says anything about the artist, i.e., the actual speech production process.

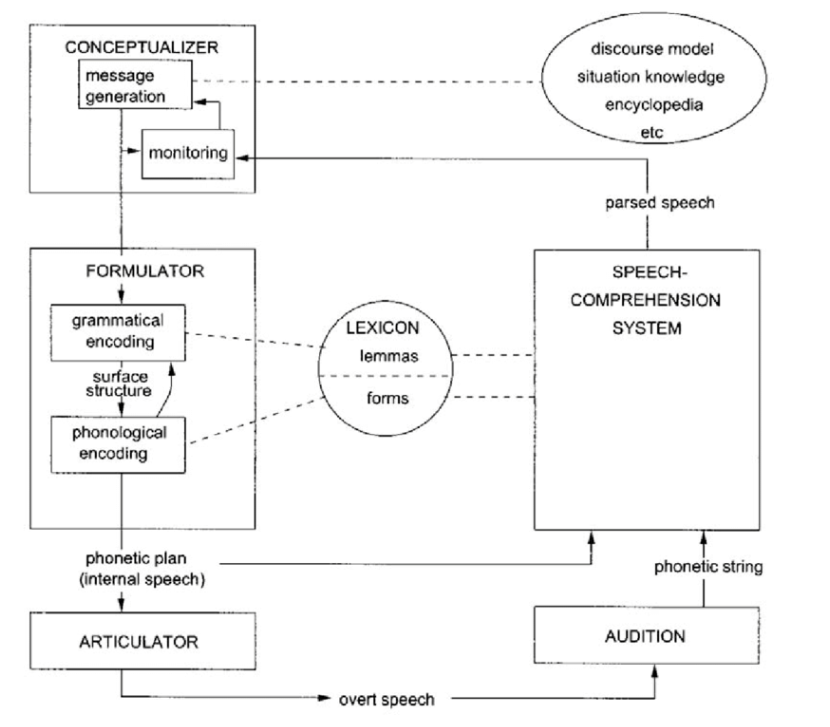

Pim Levelt is one of a few psycholinguists who worked on the issue of speech production, work that Dennett endorses. Levelt introduced a “blueprint of the speaker” where there’s no central meaner, but a system with a conceptualiser, a formalizer, articulator, as well as a discourse model and a speech comprehension system (as shown in the figure below). Despite the conceptualiser appearing to be the captain in the system, it is no more than a message generator. The conceptualiser receives parsed speech from the speech comprehension system and provides preverbal messages to a formulator, which produces what Levelt calls “internal speech” and is formed later into phonetic strings. Levelt’s hypothesis has a concept of a ‘Brainish Language’ of thought that is used only to order speech acts; “it is not a language for all cognitive activities” says Dennett.

Levelt’s model was inspired by the Von Neumann machines that Dennett referred to earlier in the book. The language of thought could be viewed as the equivalent of machine language in computers.

While Levelt’s model doesn’t clarify the role of the conceptualiser, Dennett finds it a good model to rely on for moving towards the next stage, the ‘tournament of words’. When demons and circuits that initiate drafts have something to say, they compete with each other to produce speech. This bureaucratic process is the method of selecting what to say from all of what the demons report, and could be an evolutionary process that involves collaboration between these demons.

But how can the demons have the words and grammar to produce speech? Dennett suggests employing the Levelt model but supplementing it with pandemonium. The pandemonium model is an alternative to a central meaner or dictator that constrains the demons in their activity. Jerry Fodor thinks that “language carpenters” would just execute orders to form speech. But Dennett goes further to suggest that speech production could be happening as a result of an evolutionary process, which is itself is another kind of pandemonium.

The competition between demons in this evolutionary pandemonium model is illustrated by Freudian slips. How do Freudian slips happen? Dennett mentions research by Birnbaum and Collins (1984) which shows that they’re not random or meaningless mistakes in producing speech. They are, in Dennett’s terms, “mistakes and not mistakes”. They could be evidence that the processes of producing speech run in parallel and have multiple, simultaneous goals. We may not be fully aware of what we think until we say it; Dennett quotes Bertrand Russell saying, “I did not know I love you till I heard myself telling you so”. Even the line that separates what we want to say, “preconscious fixation of communicative intentions”, and their execution into speech could be a very gerrymandered line.

By Omar Meriwani

Edited and proofread by: Damien Shingleton

0 Comments