Dennett begins his discussion of the evolution of consciousness by introducing the Baldwin Effect, which explains the impact of learned behaviour on evolution. This adaptation hastens evolution for an organism, giving it an advantage over hard-wired cousins of the same species.

An essential feature that we can assume about early organisms is reproduction: early organisms were replicators. This is a concept applicable to the evolution of consciousness, as we will learn.

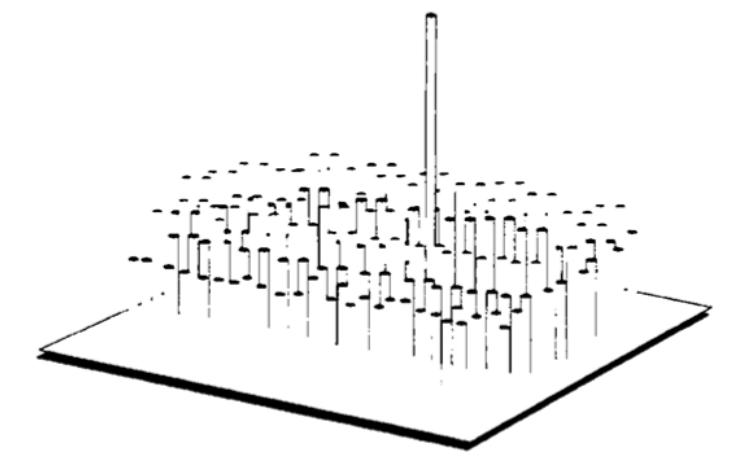

In the book, Dennett describes a plane of squares where one square is higher than its neighbours, illustrating the ‘good trick’, or plasticity (see the figure below). We could think of this as a minor rewiring between two nodes in a brain: an A and a B that can be attached in different ways or sequences. The right wiring produces a good trick that gives adaptive advantage to the organism. This good trick then continues until the whole new population fixates on it. Plasticity, or adaptability, in this context, is the good trick.

Our brains consist of many hard-wired mechanisms, and plastic ones, that are all aligned within the pandemonium architecture presented earlier in the book. The different networks, or demons, work with no central guide; their system is pandemonium. This produced an advanced hominid brain, even before language and its adaptive complexities.

The last 10,000 years saw the most recent stage of our evolution and the largest expansion of our mental powers. At this point, Dennett believes our ancestors had something new.

In addition to plasticity, sharing information became a new aspect of human thinking when language came into being. Language has a high survival value, so it is significant in enhancing an organism’s survival, and the “system would be more stable” with this capability of sharing information. As Dennett explains, communication isn’t the only important feature of language.

Dennett shares a figure of a wire that stems from the mouth to the ears; language is a system where we can broadcast a message and hear it back, like a virtual wire between two of our subsystems. Dennett calls this auto-simulation.

Cultural transmission is another tool that humans acquire due to language. That leads to a very important concept: memes.

Memes and the evolution of consciousness

Richard Dawkins introduced the term memes in his book “The Selfish Gene” in 1976. They are ideas or behaviours that spread from person to person within a culture, like genes as units of biological inheritance. They can also be seen as units of cultural inheritance.

Memes are differential. The concept of replicators applies to ideas that form into distinct memorable units, or complex ideas like wheels, clothes, or chess. Memes can be considered metaphorically as organisms. Our capacity to retain memes in the habitat of the brain is finite, so they compete in the same way as biological entities do in their own habitat.

Dennett and Dawkins represent memes in fascinating ways, ‘a scholar is just a library’s way of making another library’.

Memes could be like parasites. They could survive, reproduce, or become extinct based on their different features. Memes may be beneficial from our perspective, but not from theirs as ‘selfish replicators’. Memes may spread, while the ones we view as good may become extinct, even when we don’t like them morally and culturally. Memes can be gifts or burdens to our thinking and our memories.

Memes might restructure brains to make them better habitats. They may enhance each other’s opportunities, like the meme of education which is, as Dennett puts it, ‘a meme-implantation meme.’

Dennett introduces memes as another dimension to understand and define human consciousness: ‘human consciousness is itself a huge complex of memes that can be best understood as the operation of a von Neumann virtual machine implemented in the parallel architecture of a brain that was not designed initially for any such activities’. Von Neumann’s machine or architecture is the model of computers that existed since the early age of computer invention. The model has a memory unit, a processing unit and input and output units.

The great computational metaphor from Dennett to explain the relationship between memes as software and the brain as hardware, was this: ‘the powers of this virtual machine vastly enhance the underlying powers of the organic hardware in which it runs.’ So, the adaptive advantage of memes is the enhancement of our hardware, the brain, not just its software.

But why didn’t our ancestors have more complex tools like pistols? Why didn’t we sprout wings? If our brains have a conscious and logically advanced part, like a Von Neumann machine designed by natural selection, why don’t we have more complex tools?

The first part of the answer is that our brains, like computers, have the ability to imitate. A turning machine is an imitation machine that can imitate any possible functionality rather than having rigid software.

The second part is that, to make them capable of forming a massive parallel processing machine, is they didn’t need to have hardware specific to this task. Rather, our brains are structured by a process similar to knitting. These knitted structures can host the virtual machine that Dennett describes. Knitting can expand and replicate similar structures, but not necessarily make task-specific functionalities out of them. Instead, the virtual machine, or software, can actually perform these task-specific functions. In this way, culture can impact and edit the virtual machines later, while these machines remain hosted on the knitted structure, the hardware.

So, consciousness is better viewed as programs installed on an existing machine. Despite using computers as a metaphor here, the brain has nothing analogous to CPUs. Memes also have an important role in shaping the hardware. Unlike pistols or wings, the machine that is required for this purpose doesn’t need a jump in complexity; it can be a simple long term process, like knitting.

The results wouldn’t necessarily contain a perfect match between software and hardware. Replicating could be the only thing our machines are meant to be good at. Some of the features of the machine could be seen as no more than software viruses. Even parts of the hardware could be like parasites that exist there ‘just because they can’, as Dennett explains, and it isn’t worth getting rid of them.

By Omar Meriwani

Edited and Proofread by Daniel Shingleton

0 Comments