In Chapter 12, Dennett addresses the concept of qualia—the way we subjectively experience things. Many philosophers argue that colours, for instance, are merely mental constructs rather than real properties of objects. Some argue that certain main features, like red, might exist in nature, while others like pink arise from the way we perceive colours rather than from the inherent properties of surfaces.

Dennett counters this by reframing the debate on the features of objects and our consciousness of them. He uses the example of a robot like CADBLIND, which has a simple function to compare degrees of red and can distinguish between pink and red based on objective measurements. If a robot can perform this task using objective features then there could be an alternative way to explain how we experience things.

In 1950, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were arrested in the United States by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for espionage. The couple had worked on the Manhattan Project, the U.S. program to develop nuclear weapons. They used a clever trick—a Jell-O box—as a password for communication within their espionage network. Their goal was to provide the Soviet Union with American nuclear secrets. How is this relevant to our experiences?

The spies used cardboard pieces to form a password where the pieces matched each other because they were made of the same material and the same thing. Similarly, according to Dennett, colours and colour vision are interrelated. Earlier examples of the evolution of colour vision were represented by colour coding systems, similar to those used in hospitals. Colour coding was a ‘good trick’ in some insects to find the flowers (remember the good trick in Dennett’s evolution of consciousness). However, not all animals have colour coding or the ability to see colours or the same way.

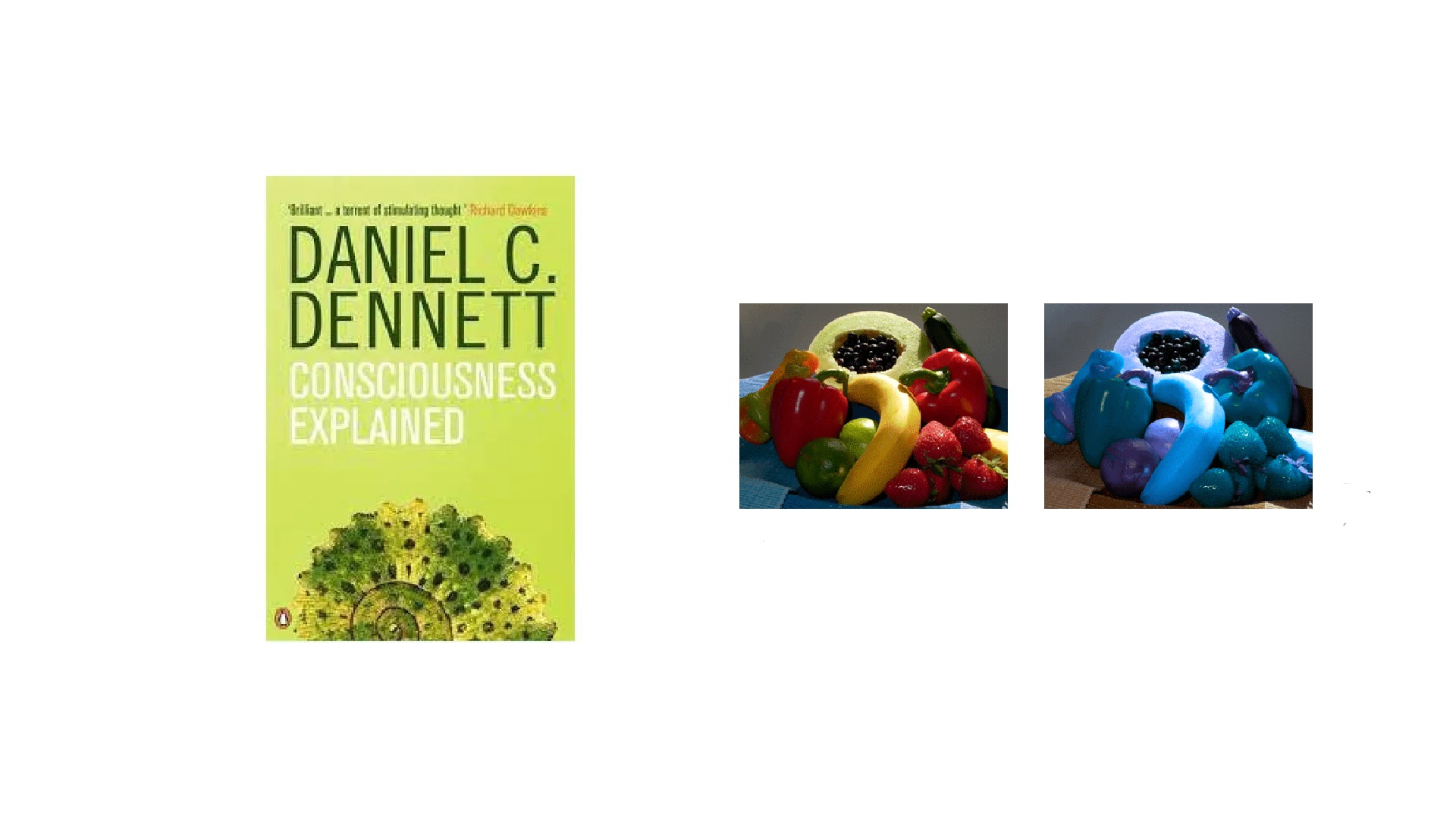

The evolution of colour vision can be illustrated by other examples such as the co-evolution of apples colouring and the fructivores. Dennet then questions: “Why the sky is blue? Because apple is red, and grapes are purple”. Our vision has developed since the time of our early ancestors, and the early color coding we had plays a role in our general color vision, including for things we don’t eat or smell, like the sky.

The Jell-O box metaphor can also be expanded to another aspect of our experience. For experiences like loveliness or joy, there must be context. Just as insects don’t evolve to be attracted to specific colors without context (e.g., for feeding), every experience must be related to a class of observers to be properly discriminated.

Many of our experiences and the ways we perceive things are innate. For example, the fear of snakes or attraction to certain colors may be inherited alerts. Similarly, our preferences and reactions can be innate and stem from a fundamental source. These innate dispositions are then shaped by cultural influences (memes) in various ways, transforming them beyond mere historical mechanical reactions. While this view might not align with qualia philosophers, Dennett has more to say about qualia and its implications..

Qualia is an experience that seems to requires a connection, or a wire point A, like the eye sensing colours, to point B, where the experience happened. Hence, there’s what looks like a network that’s attached to many things working simultaneously “multiple paths on which multiple drafts are being edited simultaneously and semi-independent” as Dennett describes. So, where would the Cartesian Theatre for this experience be? Someone might suggest that the qualia are an epiphenomenon, a byproduct of the processes like seeing colours. However, Dennett rejects the concept of qualia as an epiphenomenon.

If the byproduct of our sensations were an epiphenomenon, we would expect that inverting our experience – such as wearing inverted glasses or swapping colors like green and red – would impact that byproduct too. However, according to Dennett, qualia cannot be inverted in this way. Dennett argues that the qualia don’t exist within our brains, but instead arises from the richness of the world and what we become conscious of from in it. There is no need to impose extra complexity on the brain; our experience and the world around us are already rich and complex enough on their own.

When we see, smell, taste, or hear, we become conscious of different parts of this richness around us – or we may not, making our experience unique and ever-changing. For instance, a seasoned wine taster perceives the taste of wine differently than when they first tasted it or compared to someone who isn’t a wine expert.

Dennett borrows the phrase Semiotic Materialism from David Lodge, which suggests that what we say or write is inherently connected to the practices we descirbe. This deconstructionist idea proposes that materials and discourse share the same origin. Similarly, Dennett sees a parallel relationship between our experience and the world we experience. Therefore, we shouldn’t dismiss this relationship in favour of the Intrinsic part of our brains to explain ‘qualia’. “Qualia is replaced with complex dispositional states of the brain” Dennett summarizes the idea of this chapter.

0 Comments