It might be an unpleasant idea, but if you spit in a cup, can you re-drink your saliva? It seems like once something leaves your body, It’s no longer part of you, similar to hair or nails. This explains how we get our sense of self. Similarly, our bodies are home to billions of bacteria and viruses, some of which have become integrated into our cells, like mitochondria. This concept isn’t limited to humans; it extends back to the simplest single-cell organisms, which have basic mechanisms to avoid self-destruction. But these boundaries are not the only ones.

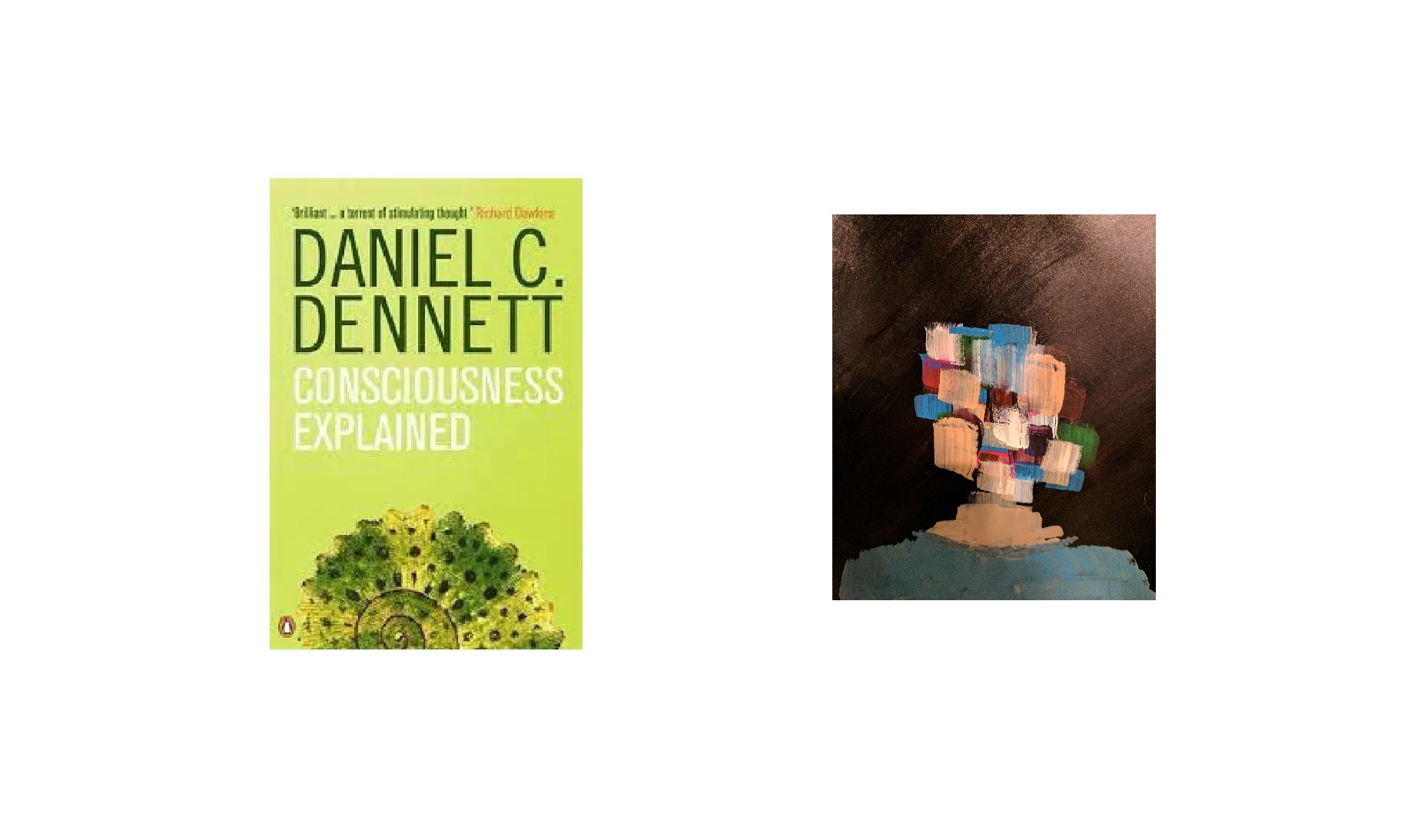

Animals extend their borders into their environments, such as houses, nests, beaver dams, and spider webs. Similarly, humans extend their boundaries through clothes, homes, buildings, and borders. However, the most significant way to establish our boundaries and sense of self is through language. We create boundaries with words, narratives, and stories. Akin to a spider’s web, we weave complex webs of discourses. But what about our internal “society of mind”, our demons, and the pandemonium model that Dennett described? Will there be a single self that emerges as a single dictator, or a Cartesian Theatre, representing our unified sense of self?

Multiple personality disorder (MPD) is a condition where individuals who have experienced severe childhood abuse may develop multiple distinct selves. While this rare medical condition doesn’t imply that everyone has multiple selves, it does challenge the notion of a singular central self. Dennett also discusses a curious case involving the Chaplin twins, Freda and Greta. These twins talk together, walk together, and do everything together. Surely, they are not connected by any telepathic force, but rather by their coordination and shared experience. Nonetheless, it is evident that such twins have a unified sense of self.

The other case that challenges the notion of the single self is the split-brain condition. In this case, the patient’s left hemisphere is separated from the right hemisphere. Some patients with this condition report experiencing multiple selves similar to those with MPD.

Dennett revisits the concept of gaps in consciousness, which he discussed in earlier chapters, and demonstrates through experiments and examples that our consciousness isn’t continuous but gappy. Such cases as MPD illustrate the effect of bifurcation that happens in consciousness here. These examples challenge, if not entirely refute, the idea of the self as a central dictator in the mind.

Returning to the concept of demons, agents, or the society of the mind in our brains. The idea of multiple selves that Dennett presented earlier doesn’t directly apply to these agents or the issuers of our multiple drafts. This concept is deeply rooted in our neural system, inherited from early organisms that had mechanisms to recognise their boundaries and avoid self-destruction. Consequently, these internal agents or demons do not have their selves, except in cases like MPD.

We are equipped with an ancient system for recognizing boundaries. While we may, in rare cases, have multiple selves, we still grapple with fundamental questions like “What is me?” or “Where are my boundaries?” Chimpanzees, for instance, can test their existence and boundaries by looking in a mirror or on a screen to determine whether what they see is “me” or not. Dennett mentions a radar system used by small boat owners that shows dots on a map. If an owner loses track of their boat on the screen where all boats are shown as dots, they can make a circle on the screen to identify which dot represents their boat.

So, what’s our experiment to know who we are? Instead of a boat’s circular movement or a chimpanzee’s mirror test, we have a wide range of actions for self-knowledge. We have narratives, stories, and identities that help us find and know ourselves. Our radar blip, akin to the radar system, is the story we tell about ourselves. You, or me, are the centre of a narrative gravity.

0 Comments