So, let’s move to the other important topic: eating disorders and their relationship to our evolutionary conditions. Does the concept of mismatch apply to them?

The answer is yes—mismatch does apply, perhaps even more significantly than to any other condition. When I teach evolutionary psychiatry, whether to fellow psychiatrists , students, or trainees, I give them examples of mismatch, and eating disorders is always top the list because they are a group of conditions that didn’t exist at all before the modern era. Take anorexia nervosa as an example: eating disorders predominantly affect women far more than men—girls and women much more than boys and men. In hospitals treating these cases, roughly ten female cases correspond to one male case. Some specialized treatment units don’t even treat men because their numbers are so small that there’s no need to allocate space for male treatment.

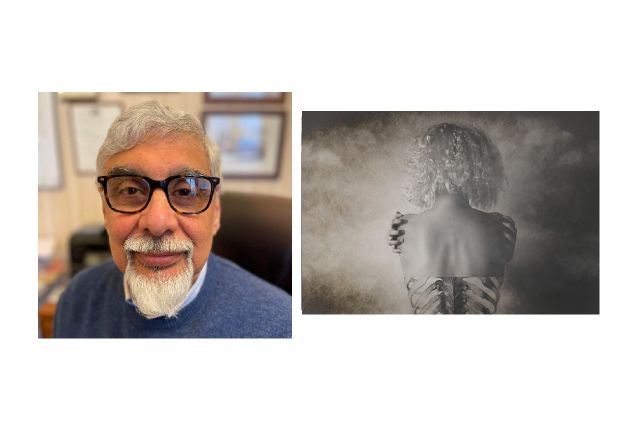

So, what are eating disorders? Most fall under anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Anorexia involves abstaining from food, which can lead to life-threatening weight loss in its extreme forms. Bulimia involves eating food—sometimes in large amounts—then purging it through vomiting or laxatives. Those affected by either condition, whether anorexia or bulimia, develop the belief that they are overweight despite being extremely thin. When they look in the mirror, they see themselves as fat, a perception especially prevalent among women. These are the most extreme cases, potentially life-threatening, and anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder.

Another striking aspect is that eating disorders don’t occur outside the West or countries that fully adopt Western culture and lifestyles. Thus, their prevalence in non-Western countries—Islamic countries as a comparable example—is very low because these societies generally haven’t adopted the Western way of life. So, despite adopting some modern elements like cars, housing, or certain clothing, their lifestyle and social organisation remain very conservative. Take Iraq or other Middle Eastern countries: they are generally conservative, maintaining a non-Western lifestyle where women’s freedoms are shaped by local customs, not Western individualism. Regarding eating disorders in Iraq, I have more information about it than other Arab countries because I visit frequently and discuss it with psychiatric colleagues there. Cases are extremely rare—so rare that some specialists in Iraq have never seen a single case.

Another example: severe eating disorder cases, especially anorexia—the most dangerous type—bulimia is less lethal as it doesn’t involve total food abstinence, whereas anorexia can drastically reduce weight to life-threatening levels. In 2023, a study in the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ journal (the BJPsych Bulletin) reported on all patients in UK hospitals requiring nasogastric tube feeding because they’d completely stopped eating. To save their lives, they are fed liquids through a tube from the nose to the stomach. They identified around 115 cases across Britain. Of these, 99% were female and only 1% male. In Iraq, to my knowledge, there isn’t a single case of tube feeding due to anorexia. I believe—though I lack definitive proof—that this applies to other Middle Eastern countries too. And the lack of such severe cases, in my opinion, is a real phenomenon and not simply a lack of identification. These cases simply do not exist in these countries as, if they did, they could not be overlooked or ignored as this can lead to the death of these young women. It is highly implausible that a family would neglect a dying daughter without seeking help, so their absence from hospitals likely means they do not exist.

However, even in Britain, these cases didn’t exist 50 years ago—they were either very rare or non-existent. Thus, it is likely that mismatch plays a huge role, as there’s a clear disparity in food abstention or eating disorder rates across societies and countries, with women being disproportionately affected. My theory is that eating disorders aren’t literally about food but are a set of conditions arising from what I call “sexual competition among women.” What causes this competition? It’s the Western social condition relying on individualism and freedom of choice, where families play little role in shaping gender relationships, leaving individuals fully responsible for their relationships. This responsibility comes at a cost: a “relationship or mate market” where certain traits increase or decrease an individual’s value. For women seeking relationships, youth and good health become the critical factors.

When I discuss such conditions with Iraqi colleagues, they find them surprising, especially those unfamiliar with Western life or practices. Several social conditions—like individualism and lack of family involvement in relationships—oncrease individual competition among women. In societies with high levels of individualism, a person faces others or society alone, whereas in less individualistic societies, they see themselves as part of a group, family, or tribe. For example, a woman seeking a partner—whether for marriage or otherwise—in individualistic societies, it’s a personal endeavour with minimal involvement from others, even close family. In non-individualistic societies (more collectivist societies), marriage is a family decision, even involving the extended family, making the search for a partner a collective, not individual, matter. Competitive factors go beyond beauty and youth—though these are still very important—like reputation, which might be of primary importance in our societies. A family’s reputation may have a crucial role in relationship decisions whereas such considerations are nearly absent in individualistic societies.

I am not here meaning to praise or criticize any societal structure—each has its pros and cons. My point is that eating disorders appears to be strongly linked to the Western individualistic societal arrangements. Although, of course, collectivist societies have their own problems and downsides, which I am not going to go into. My purpose is simply to highlight how these social arrangements affect the risk of specific psychiatric conditions and specifically eating disorders.

Omar: A question may be asked, “Doctor, sexual competition and modern life could lead to many things—why specifically eating disorders in some people?” We’ve focused on competition, modern life, and individualism, but if we try to understand what eating disorders do to the brain—are there biological or genetic factors?

Dr Riadh: In principle, yes, but it’s still largely unknown. Studies suggest competition among women causes psychological stress leading to mental disorders, including eating disorders, depression, and anxiety, but this might not suffice, as eating disorder specialists aren’t typically interested in this evolutionary theory and haven’t invited me to speak at their conferences—a surprising neglect of the evolutionary perspective in psychiatry. The full details of how the stress of competition can lead to eating disorders and why this is so can be found in my published papers that are available online.

When discussing evolutionary psychiatry, it’s often compared to traditional talking therapies or medication-based psychiatry. In Iraq and some Arab countries, psychiatrists themselves provide talk therapy rather than specialized therapists. So, what does evolutionary psychiatry offer? Are there prospects for developing drugs, surgical interventions, or new therapies?

The answer might disappoint some: there are no drug or surgical treatments based on evolutionary psychiatry. Surgical interventions in psychiatry have largely proven ineffective and been abandoned, but evolutionary psychiatry is primarily a research field offering a framework for deeper understanding of disorders. It may not directly yield treatments but is as valuable as genetics, which hasn’t produced a psychiatric treatment despite massive investment (many billions of dollars). Explaining conditions to patients from an evolutionary perspective can be therapeutic itself, and there are two evolution-based talk therapies: Compassion-Focused Therapy by Paul Gilbert and Evolutionary-Informed Cognitive Behavioural Therapy by Mike Abrams. For those interested, I co-authored a book with the Royal College and Cambridge University, available on Kindle and the EPSIG UK YouTube channel, hoping to encourage discussion of real science in Arabic.

0 Comments