From the dark depths of childhood and upbringing in the Arab world, To Choose Madness traces the unfortunate path of a “sane” person through that turmoil. Parental violence — where a belt or a whip may do more damage than the secret prisons of authoritarian Arab regimes — is at the heart of this story. The primary oppressive system leads Hatim bin Abdullah, the fictional Saudi protagonist of the novel, to learn lying, experience panic attacks, anxiety, major depression, poor career choices, deep shame, and ultimately to choose madness.

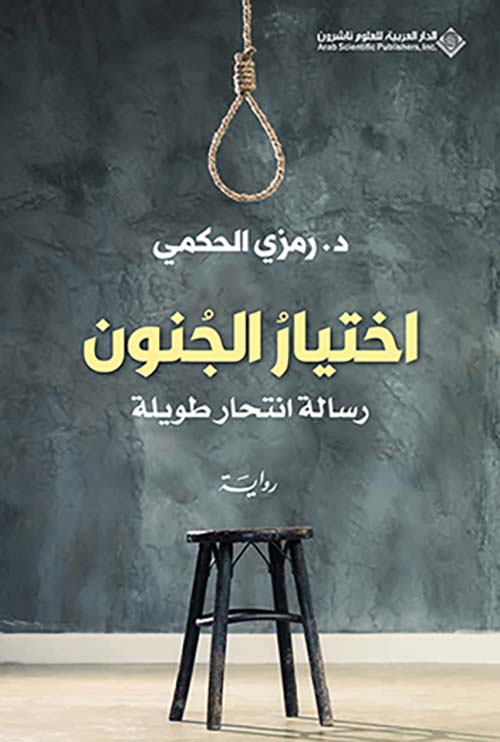

But what does it mean to choose madness? Can we write scientifically about “madness”? In truth, the author is not a typical writer — he is a psychiatrist who guides us through the most intricate details of psychiatric medications and addiction, in a way only a doctor and a writer can. Ramzi Al-Hakami, our colleague at Real Sciences, writes the first Arab psychological epic, and I am confident in calling it that — just as I am confident in the scientific accuracy of its threads and their necessity for the Arab reality and for Arab psychological culture.

A Wounded Childhood

Hatim bin Abdullah documents his life in the form of a suicide letter. While most people’s lives are recorded by their achievements or moments of glory, Hatim describes his life as a series of sins. The first “sin” was lying — but why? Because Hatim was sexually harassed by a schoolmate. His father’s response was to whip him until he urinated on himself, leaving behind eternal terror that would later manifest in multiple psychological syndromes — compounded by the dozens of times his father repeated such brutality.

It is difficult to find studies in the Arab world that cover this kind of sexual abuse, but there are many studies on parental violence, often reaching shocking levels — and the news has covered stories like this across the Arab world: the child who skips school to hide the torture marks from the teacher.

Ramzi takes us through the life of someone whose story might appear briefly in the news — someone we feel disturbed hearing about — but we never think about the rest of their life. There are many such people around us.

Hatim’s father, Abdullah, says to him years later, after several collapses in Hatim’s life: “I was hard on you because I love you, to make you the best man you could be.” How often we’ve heard this tragic narrative?

In many domestic violence stories I’ve heard personally, the child ends up urinating or defecating involuntarily after a beating with a belt or electrical wires — exactly like what happens in prisons. Parents who say things like this were often victims themselves — they believe they’re raising a “real man,” or “zalme” as expressed in Iraqi and Syrian dialects. Those who think they’ve survived their own trauma often recreate it for their children. The deliberate transmission of psychological trauma feels almost like genetic or memetic inheritance: studies show that parents who experienced childhood violence are statistically more likely to inflict it on their own kids.

Did all these parents really want their children to become better people — or “real men”? Many children don’t survive such extreme cruelty — Hatim bin Abdullah was one of them.

Not all of Hatim’s behaviors stem from his abuse, or from the attempted rape, or from a society that offered no sense of safety (Hatim grew up in a poor village in the southwest of Saudi Arabia). One of his “sins” was enacting historical Islamic battles alone — role-playing. But this innocent act led to another torture session by his father. (I use prison terminology deliberately — every parent should see these acts for what they really are.)

Does role-playing or talking to oneself deserve that? Years ago, Ramzi wrote an article defending self-talk as a natural and healthy behavior. Role-playing is also a natural part of childhood development. Yet the aggressive response to such behavior — often triggered by neighbors reporting to the parents — reflects a traditional Arab system that makes us question why we only blame state security agencies.

To Choose Madness places the blame on the broader, more pervasive structure. Have you, as a reader, ever suffered from these “security reports” by nosy neighbors or relatives?

Hatim’s life is defined by his “sins” and the psychological crushing he endured — like the trauma after re-enacting the Battle of Uhud alone in his village. These sins are not fleeting guilt; they are deep-rooted shame. For Hatim — and many like him — this shame is eternal. Shame about sex, about masturbation, about entirely normal things.

The Psychological Journey

The book offers a detailed account of panic attacks, anxiety, depression, and more — including physical symptoms, worldview shifts, emotional states, and behaviors. This is not from an average writer, but a psychiatrist who has listened to thousands of patients and brings both personal experience and vast knowledge.

In addition to his efforts in communicating science to Arabic readers (e.g., Real Sciences), Ramzi explores recurring patterns in the lives of those with psychological crises — such as being offered religious advice instead of real help. The book portrays Hatim’s deep immersion in religion — becoming a “mutawa” (pious man) for a period — not as a direct result of upbringing, but as part of his journey. Some studies suggest a correlation between trauma and increased religiosity, but the relationship remains inconclusive.

Hatim is even subjected to ruqyah (Islamic spiritual healing) by his family as a “cure” for his madness, which is really just suppressed rage toward his arrogant father:

“The sheikh rolled up his sleeves and began to touch me while reciting Quranic verses. I said nothing. My eyelids didn’t even flicker. The strangest thing was that my father was the only one who reacted — he collapsed to the ground, as if possessed.”

The book touches on little-known anxiety symptoms – in the Arab world at least – like teeth grinding during sleep, which becomes so loud that it drives people away from Hatim. It discusses unbearable fear while asleep, constant fatigue, muscle aches, dry mouth, and nighttime thirst. Don’t you know someone who suffers like this?

Hatim also behaves erratically in school, such as throwing his pen at a teacher during a debate about a subject in Arabic grammars. This resonates with how we often see extreme behavior — in school, politics, or sectarian debates. Is this connected to early trauma? Or to the psychological structure it built — a complex blend that cannot be reduced to mere “depression” or “anxiety”?

The book offers a positive portrayal of psychiatry and proper mental health interventions. It discusses medications — Cipralex for anxiety and Prozac for depression — which help Hatim immensely. I haven’t seen a more nuanced depiction of psychiatric medications — their side effects, benefits, and how their impact unfolds — than in Ramzi Al-Hakami’s elegant, scientific prose.

The lifelong presentation of Hatim’s condition reflects the complexity of psychological issues, showing that medication and therapy must be contextualized properly. Psychiatry can help, but healing is not like curing a headache — it’s not like any other medical field. Hatim doesn’t necessarily take a positive path, but we see that the psychiatrist was perhaps the only positive person in his life. Hatim tells his doctor:

“I realized I had the right to hear and see, rather than spending my life trying to re-enact every whip my father laid across my back. In that moment, I understood that the terror I lived — my heartbeat, my breathlessness, my numb limbs, my back pain without injury or disease — meant that I was still stuck in the scene of Hatim the child, shielding himself with tiny hands from a father who could only deal with his complexes by devouring one of his children like a frightened pig.”

Before such a text, we don’t need scientific studies to validate everything — the human experience itself is the evidence. To quote from our book in Real Sciences Psychotherapy: How We Face Psychological Suffering Through Science:

“People with four adverse childhood experiences are four times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes and three times more likely to suffer from cardiovascular disease. Those with six experiences in the U.S. may die 20 years earlier on average. They’re also three times more likely to never feel relaxed and six times more likely to never feel optimistic. Addiction rates to cocaine and heroin also skyrocket compared to non-traumatized individuals.”

Addiction: The Dilemma of Our Time

The book’s next phase deals with addiction. For those unfamiliar with qat, this book introduces the plant in detail — common in Yemen and parts of Saudi Arabia like Jazan, where the story is set. The book vividly captures the stages of its effect — from euphoria to intellectual elevation. It may seem like the book glorifies qat, but the reader eventually grasps the bitterness of the experience, much like with other drugs.

The book also explores the black market for psychiatric meds, Hatim’s break from his doctor, and experimentation with other psychoactives like hashish. Some of the best philosophical or humorous dialogues happen during qat sessions, adding depth and reality to the experience.

It also illustrates how addiction affects relationships, coping with loss, and financial crises. Addiction, along with its psychological and physical impacts, doesn’t necessarily mark the end — but it adds significant layers to the overall experience.

Madness

In popular culture, “madness” is tied to ignorance about mental health — where people divide others into the “sane” and the “mad.” So how does a psychiatrist choose to title a book To Choose Madness? It’s not just a title — it’s a challenge.

What is madness? The book references the Rosenhan experiment, where actors feign mental illness and are admitted to psychiatric institutions. The book stands up for psychiatry, and for the mad. In a scene, trainee doctors label someone with various disorders, but the senior psychiatrist corrects them — the man isn’t mentally ill. Even doctors can fall into the trap of using primitive labels — it takes an experienced practitioner to see clearly. Will we find such doctors in the Arab world? One hopes so.

The book also explores the legal and social treatment of madness — how people can be treated more leniently, harshly, or neglected simply because they “look” mad — and how laws can overlook or dismiss actions and words based on perceived mental state.

Language

The book dives deeply into language’s role in perception and mental health. Hatim studies language, but his engagement with it goes far beyond academia. Like many, he was forced by his father to study medicine — but chose language instead, a rebellion against tyranny and a pursuit of the self. The taxi driver taking him to college is the final echo of the societal voice that expects every smart student to study medicine.

The dialogues explore not just abstract language, but Arabic — in jokes, flirtation, trauma, therapy, and qat sessions.

Language becomes a living being, described poetically and philosophically. For example:

“I became addicted to reading philosophy when language no longer had anything to say to me.”

“My grief is savage, pre-linguistic — predating language by millions of years.”

The author captures mental experiences that language cannot reach, echoing thinkers like Daniel Dennett, who said that not all mental processes need to have language. I quote:

“But the limitations of language in portraying reality pose a challenge to the speaker when trying to describe a man slitting his own throat in a way that avoids passive voice. One might say: ‘He slit his body or his throat, so he killed himself,’ or ‘He self-died (استمات?)’ — but none of this conveys the raw truth. We lack a verb that captures the full essence of suicide without relying on metaphor or grammatical accommodation. Even Latin (suicide = sui + cide) shares this problem. According to the author’s research, no language in the world has a direct verb for suicide that bypasses this limitation.”

I decided to leave the discussion on language and mental health from this book to another article.

Conclusion

The book gives fair attention to all factors shaping a difficult life. Family is the first — Hatim says to his father in their only real conversation: “My illness is my family issues,” in response to his father’s suggestion to set those issues aside and focus on his problem.

This book is not a case file of mental disorders. It’s a profound exploration of the human experience — love, psychoactive substances, psychiatric medication, friendship, loss, and philosophical ecstasy.

Family, friends, society, religion, medicine, language — and above all, personal choices — each plays a role in Hatim’s journey and fate. The book deserves to be read not just as a dose of philosophical pleasure, but as a rich blend of culture and science that one may not find elsewhere — at least not in Arabic.

References:

[1] Greene, Carolyn A., et al. “Intergenerational effects of childhood maltreatment: A systematic review of the parenting practices of adult survivors of childhood abuse, neglect, and violence.” Clinical psychology review 80 (2020): 101891.

[2] Tekinbas, Katie Salen, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of play: Game design fundamentals. MIT press, 2003.

[3] Trevino, Kelly M., and Kenneth L. Pargament. “Religious coping with terrorism and natural disaster.” Southern medical journal 100.9 (2007): 946-947.

[4] عمر المريواني، العلاج النفسي: كيف نواجه المعاناة النفسية عبر العلم، العلوم الحقيقية، لندن، المملكة المتحدة

[5] كتاب شرح الوعي لدانييل دينيت: قراءة في الفصول الست الأولى من الكتاب، العلوم الحقيقية

0 Comments